Desmond Clifford in Nation.Cymru

Peter Finch is a poet because he's a poet. No one told him to, he passed no exam, entered no guild. He's a poet because he is, and now he's been at it for as long as Tom Jones has been singing.

Born in 1947 he grew up in provincial Cardiff post-war austerity. He belonged to a small community who brought the 60s to Wales, challenging my cultural theory that Wales time-warped from 1959 to 1971 without experiencing the 60s at all; and, having arrived in 1971, stayed there until the Miners' Strike in 1984.

Finch is a poet, a writer, bookseller, editor and part of a generation of "literary entrepreneurs" without whom the whole concept of Welsh writing in English would be hopelessly stunted. The lonely business of writing is just the tip of the iceberg.Eco-system

The world of promoting, publishing, book-selling, editing, performing, arguing, anticipating, complaining, advocating, creates an eco-system for a literature with at least some notion of coherence and community. Thanks to people like Finch, Meic Stephens (Wales' Dr Johnson), Ned Thomas, Dai Smith, M Wynn Thomas and others, it is not vacuous to talk of a Welsh literary scene in English. It may be fragile - marketing and distribution remain problematic - but it exists and is lively.

In recent decades Finch has become as well-known for his non-fiction as his poetry. He virtually invented a new Welsh genre of "psycho-geographies" with the Real Cardiff series, a form of travel guide based on walking around his home town with his eyes open and his brain switched on. The franchise has broadened across Wales and beyond.

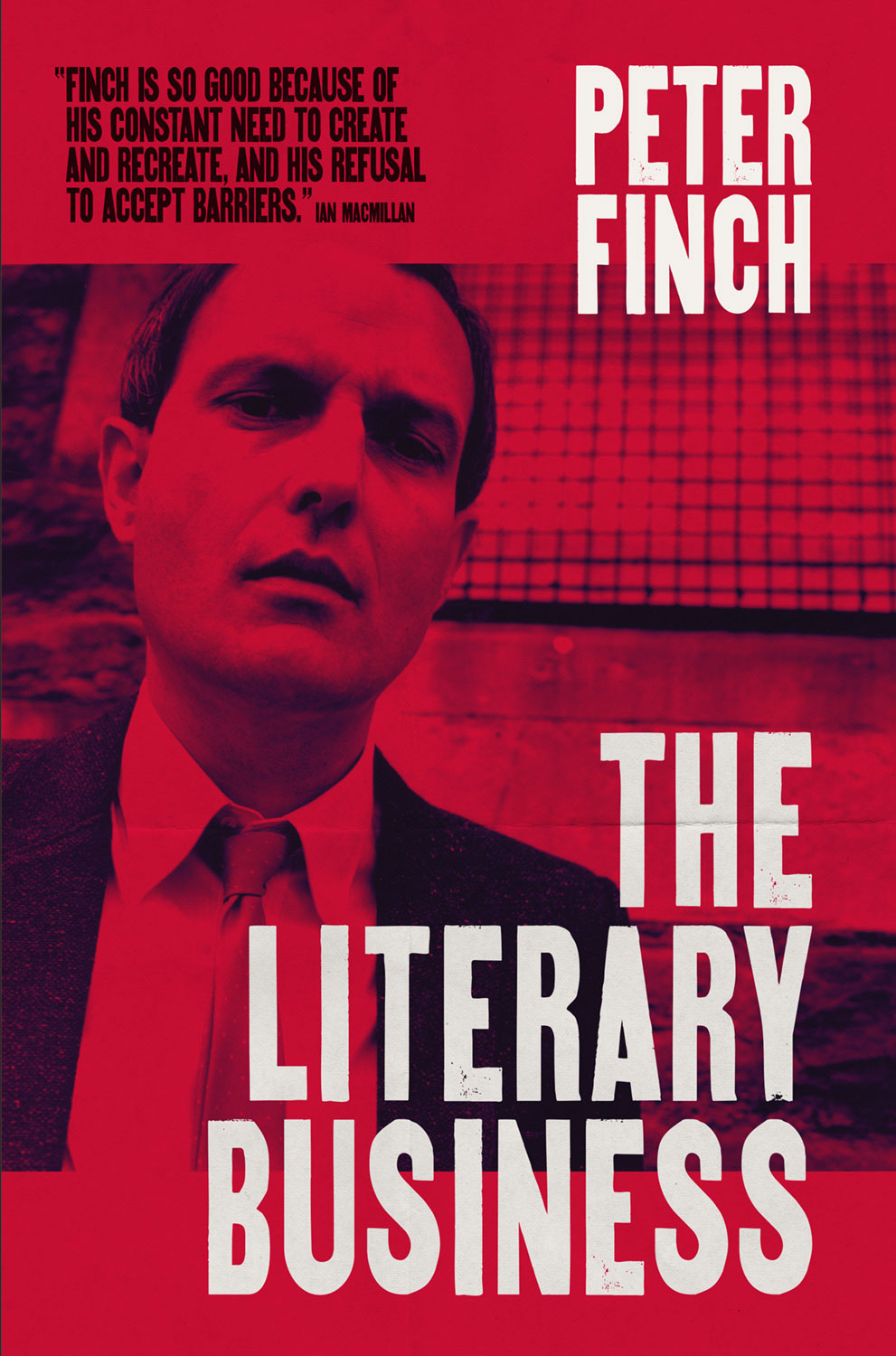

"The Literary Business" is an episodic memoir of the literary pathway he followed, mostly without compass or map, over half a century and more. In the same way that scribes wrote the lives of saints to guide and inspire the faithful, so Finch's memories can help guide today's writers and literary creatures.

Launching the avant garde poetry magazine "Second Aeon" in 1966, still in his teens, Finch rode the last great wave of the literary periodical. "Launching" suggests print-runs, adverts and a cocktail party for movers & shakers.

In fact, Peter cobbled together a few mimeographs and hawked them where he could. In time, poetry from around the world found its way to him and "Second Aeon" filled out to more than a hundred pages per edition, with increasingly professional production and subscription demand met by Peter stuffing the post boxes of Llandaff North.

From the 1960s onwards poetry fell into roughly two camps. There is the more formal poetry linked to tradition, written with conscious respect for form, structure and poetic convention. For all his irreverence and accessibility, Harri Webb is an example of this kind of poet. Then there is experimental poetry, written without much respect for form and tradition, often described as "avant-garde"; abstraction and challenge are as important as the conventional and elusive search for meaning. Peter Finch is in this camp, with a body of work often linked to performance and props.

"Booksellers and authors live on adjacent, but different, planets. The booksellers on Mars, the writers on Venus." Notwithstanding his own analysis, Finch commanded an inter-planetary module to travel the lightyears between the planets of war and love.

Bookseller

In the best romantic tradition, he fled an accountancy traineeship to become a bookseller, for many years managing Oriel, owned by the Arts Council in Cardiff.

Controversy hung over it; even the radical bohemians had some doubts about what could loosely be called a state-controlled commercial venture. Equally, distribution and marketing of Welsh books are as vital as their writing, and the commercial sector - very properly - aims to shift stock speedily and keep the tills busy. Even with benign booksellers, it's a tremendous challenge to find space for Welsh material amid the ever-expanding universe of books in English.

The publication rate for Welsh books, in both Welsh and English, is fairly healthy. The greater challenge is creating a coherent identity and visible availability for them; that's the market-failure which Oriel filled, and its demise was a loss.

Oriel was Meic Stephens' idea and Finch is generous with praise for his work promoting Wales' literature, "Our great orchestra was Meic's belief, and he spent much of his time fighting this corner." Much of the "literary infrastructure" built over the last fifty years arose from the conviction of small groups who made things happen. Finch and Stephens were central to this work and their partnership was strong, even though they occupied different parts of the forest; Meic was intuitively a supporter of more traditional literature while Peter was happiest among the ruffians.

Welsh literature

There's a long history behind the epithet "Welsh literature". The distinction is that Welsh language literature dates back continuously to the sixth century and counts among the world's oldest living literatures, while what we now clumsily call "Welsh literature in English" dates back, with some caveats, around a hundred years. Finch says of the 1970s/80s, "The writers in Welsh, the elder Cymry, wanted little to do with the more free-wheeling Welsh writers who wrote in English. The English-language writers regarded their Welsh-medium counterparts as distant and old-fashioned."

There is a conviction among some that the Welsh-language is the senior partner in an elusive cultural sense. The angst around this debate has diminished markedly over the decades for a variety of reasons, including a stronger general sense of Welsh political identity which renders such squabbles silly and destructive, but also the development of support and recognition for both languages. Nevertheless, I yearn for the day when we just refer to "Welsh Literature" and allow the context to determine whether it's in English or Welsh.

Finch's prose is brisk, breezy and business-like. I was about to comment on a certain detachment in his work, as if he's keeping the world at bay, and then I came across "How The Poems Arrive(1)", an essay on his father's death and his own divorce unfolding at the same time. It's searing. As he says, "Recollection is a fine activity, but it's best not carried out too often."

Finch nominated RS Thomas for the Nobel Literature Prize every year as part of his job leading a literary quango (I wonder if the citations still exist?). RS never won it (worse writers have: Jon Galsworthy, Pearl Buck, for a start) but we learn that Harri Pritchard Jones proposed a statue be built between the Millennium Centre and the new Senedd. It was excellent idea, but we ended up with an out-of-place Ivor Novello statue instead. I am absorbed by Cardiff's weird statue landscape; the map is bizarre and needs to be entirely re-curated to reflect better the national picture.

DIY energy

Finch's account of the funeral in 1986 of John Tripp, riotous in life as in death, is hilarious and, in a way, elegiac. Finch avoids romanticising the past. Yet Tripp's passing, albeit premature, stands symbol for a generation of "Anglo-Welsh" poets, as opposed to what we call them today, and a climate and a way of doing things. The Beat spirit of the 50s and 60s energised experimental poets into being, the DIY energy was propelled forward again by punk and sustained the spirit through the frightful 1980s.

In Devolution Wales, poetry is accommodated in the national structure. A poet's words (Gwyneth Lewis) are cast into the huge wall of the Millennium Centre. Poets read their work in the Senedd, prizes are awarded, publications supported (and then not; the nation's rulers are capricious), a national poet is appointed. A sense of recognition and respectability of sorts attaches to poetry. All good, all good. And yet…

I thoroughly enjoyed this book from start to finish. If you're remotely interested in Wales' literature and how it developed - "it" being the nuts, the bolts, the print, the shelves, the cash till, the stock control, the Sellotape - you'll love it. If not, it's simply a rollicking account of social and cultural Wales this last half a century. Finch deploys the right amount of irreverence and respect to tell his stories. He has no declared heroes but no declared enemies either; he sees the world through a cool and appraising eye.

As for Finch himself, he is established as much for prose now as poetry. He's a poet of a generation which furrowed its brow very intently on the identity question; Peter's brow is entirely un-furrowed, and he wears Wales lightly. He belongs to the universal experience of poetry. I'll stick my neck out here. I think RS Thomas is a better poet. But if you dropped them both in the Gobi Desert and asked them to do a reading, I reckon Peter would still make some sort of sense to the nomads.

The Literary Business is published by Parthian Books and can be purchased here and at all good bookshops.

If you like what

you read then

why not buy a

Peter Finch

book. Full

bibliography

and ordering

details here